Beer Street And Gin Lane

Beer Street and Gin Lane (1751)

Beer Street and Gin Lane are two prints issued in 1751 by English language artist William Hogarth in support of what would go the Gin Act. Designed to be viewed alongside each other, they describe the evils of the consumption of gin equally a contrast to the merits of drinking beer. At almost the same time and on the aforementioned bailiwick, Hogarth'southward friend Henry Fielding published An Inquiry into the Tardily Increase in Robbers. Issued together with The Iv Stages of Cruelty, the prints continued a motion started in Industry and Idleness, away from depicting the laughable foibles of fashionable club (as he had washed with Matrimony A-la-Manner) and towards a more cutting satire on the problems of poverty and criminal offense.

On the simplest level, Hogarth portrays the inhabitants of Beer Street every bit happy and healthy, nourished by the native English ale, and those who live in Gin Lane as destroyed past their habit to the foreign spirit of gin; but, as with so many of Hogarth'south works, closer inspection uncovers other targets of his satire, and reveals that the poverty of Gin Lane and the prosperity of Beer Street are more intimately connected than they at first announced. Gin Lane shows shocking scenes of infanticide, starvation, madness, decay, and suicide, while Beer Street depicts industry, health, bonhomie, and thriving commerce; merely there are contrasts and subtle details that some critics[ citation needed ] believe allude to the prosperity of Beer Street as the crusade of the misery found in Gin Lane.

Groundwork [edit]

Gin Craze [edit]

The gin crunch was severe. From 1689 onward the English government encouraged the manufacture of distilling, as information technology helped prop upwards grain prices, which were so low, and increase trade, particularly with England's colonial possessions. Imports of French wine and spirits were banned to encourage the industry at domicile. Indeed, Daniel Defoe and Charles Davenant, among others, particularly Whig economists, had seen distilling equally i of the pillars of British prosperity in the balance of trade.[1] (Both after changed their minds — by 1703 Davenant was warning that, "Tis a growing fad among the common people and may in time prevail as much as opium with the Turks,"[2] while by 1727 Defoe was arguing in back up of anti-gin legislation.[iii])

In the heyday of the industry there was no quality control whatever; gin was oft mixed with turpentine, and licences for distilling required but the application. When it became apparent that copious gin consumption was causing social problems, efforts were made to command the production of the spirit. The Gin Act 1736 imposed loftier taxes on sales of gin, forbade the sale of the spirit in quantities of less than two gallons and required an annual payment of £fifty for a retail licence. These measures had picayune consequence beyond increasing smuggling and driving the distilling merchandise surreptitious.[4]

Various loopholes were exploited to avert the taxes, including selling gin nether pseudonyms such as Ladies' Delight, Bob, Cuckold's Delight, and the none-too-subtle Parliament gin.[5] The prohibitive duty was gradually reduced and finally abolished in 1743. Francis Identify after wrote that enjoyments for the poor of this time were limited: They had often had only two: "sexual intercourse and drinking," and that "drunkenness is by far the most desired" every bit it was cheaper and its effects more than enduring.[6] Past 1750 over a quarter of all residences in St Giles parish in London were gin shops, and most of these too operated as receivers of stolen goods and co-ordinating spots for prostitution.[7]

Prints [edit]

The two prints were issued a calendar month after Hogarth'southward friend Henry Fielding published his contribution to the debate on gin: An Inquiry into the Late Increment in Robbers, and they aim at the same targets, though Hogarth'southward work makes more of oppression past the governing classes as contributing factor in the gin craze, and concentrates less on the choice of criminal offence as a ticket to a life of ease.

Hogarth advertised their event in the London Evening Post between fourteen and xvi February 1751 alongside the prints of The Four Stages of Cruelty, which were issued the post-obit week:

This Solar day are publish'd, Price 1 s. each.

Two large Prints, design'd and etch'd past Mr. Hogarth called

BEER-STREET and GIN-LANE

A Number will be printed in a better Manner for the Curious, at 1s. 6d. each.

And on Th post-obit volition be publish'd four Prints on the Subject of Cruelty, Cost and Size the aforementioned.

Due north.B. Equally the Subjects of these Prints are calculated to reform some reigning Vices peculiar to the lower Course of People, in hopes to return them of more extensive utilise, the Writer has published them in the cheapest Manner possible.

To be had at the Golden Head in Leicester-Fields, Where may be had all his other Works.[viii]

The prints, similar The 4 Stages of Cruelty, had moralising verses composed by Rev James Townley and, on the surface, had a similar intent — to shock the lower classes into reforming. Engraved straight from drawings, no paintings of the two scenes exist, although there are preliminary sketches.[9] By reducing his prices, Hogarth hoped to reach "the lower Class of People", and while one shilling was notwithstanding prohibitively expensive for most of the poor, the lower prices did allow him to attain a larger market, and more than chiefly rendered the prints cheap enough to brandish in taverns and coffee houses before a wider audience. Hogarth also had an heart on his copyright: the lower prices meant there was less hazard of the images existence reproduced and sold without Hogarth's permission. Although Hogarth had been instrumental in pushing through the Engraving Copyright Act 1734, so much so that the Act is commonly known as "Hogarth'southward Human activity", keeping costs down provided further insurance confronting piracy.

Gin Lane [edit]

Set in the parish of St Giles — a notorious slum district that Hogarth depicted in several works effectually this time — Gin Lane depicts the squalor and despair of a customs raised on gin. Desperation, decease and decay pervade the scene. The only businesses that flourish serve the gin manufacture: gin sellers; a distiller (the aptly named Kilman); the pawnbroker where the acquisitive Mr Gripe greedily takes the vital possessions (the carpenter offers his saw and the housewife her cooking utensils) of the alcoholic residents of the street in return for a few pennies to feed their addiction; and the undertaker, for whom Hogarth implies at least a handful of new customers from this scene alone.

Most shockingly, the focus of the picture is a woman in the foreground, who, addled past gin and driven to prostitution by her addiction — as evidenced past the syphilitic sores on her legs — lets her baby slip unheeded from her artillery and plunge to its expiry in the stairwell of the gin cellar below. One-half-naked, she has no business concern for annihilation other than a pinch of snuff.[a] This mother was non such an exaggeration as she might appear: in 1734, Judith Dufour reclaimed her two-twelvemonth-old daughter, Mary, from the workhouse where she had been given a new set of apparel; she then strangled the daughter and left her torso in a ditch and so that she could sell the clothes (for 1s. 4d.) to purchase gin.[10] [11]

In another case, an elderly woman, Mary Estwick, let a toddler burn to death while she slept in a gin-induced shock.[12] Such cases provided a focus for anti-gin campaigners such every bit the indefatigable Thomas Wilson and the image of the neglectful and/or calumniating mother became increasingly central to anti-gin propaganda.[12] Sir John Gonson, whom Hogarth featured in his earlier A Harlot's Progress, turned his attention from prostitution to gin and began prosecuting gin-related crimes with severity.[13]

The gin cellar Gin Royal below advertises its wares with the slogan:

Drunk for a penny

Expressionless drunk for twopence

Clean straw for nothing

Other images of despair and madness fill the scene: a lunatic cavorts in the street, beating himself over the head with a pair of bellows while holding a baby impaled on a fasten — the dead child'southward frantic mother rushes from the house screaming in horror; a hairdresser has taken his own life in the dilapidated attic of his barber-shop, ruined because nobody can afford a haircut or shave; on the steps, below the woman who has let her infant autumn, a skeletal pamphlet-seller rests, perhaps dead of starvation, as the unsold moralising pamphlet on the evils of gin-drinking The Downfall of Mrs Gin slips from his basket. An ex-soldier, he has pawned most of his apparel to buy the gin in his handbasket, next to the pamphlet that denounces information technology. Next to him sits a black dog, a symbol of despair and depression. Outside the distiller a fight has broken out, and a crazed cripple raises his crutch to strike his bullheaded compatriot.

The Kickoff Stage of Cruelty Tom Nero is at the heart torturing a domestic dog.

Images of children on the path to destruction also litter the scene: aside from the dead infant on the spike and the child falling to its death, a baby is quieted past its female parent with a cup of gin, and in the background of the scene an orphaned infant bawls naked on the floor equally the torso of its mother is loaded into a coffin on orders of the beadle.[14] Two young girls who are wards of the parish of St Giles — indicated by the badge on the arm of one of the girls — each accept a glass.[15]

Hogarth also chose the slum of St Giles every bit setting for the kickoff scene of The Four Stages of Cruelty, which he issued almost simultaneously with Beer Street and Gin Lane. Tom Nero, the central grapheme of the Cruelty series wears an identical arm badge.

In front of the pawnbroker's door a starving boy and a dog fight over a bone, while next to them a daughter has fallen asleep; approaching her is a snail, allegorical of the sin of sloth.[xvi]

In the rear of the motion-picture show the church of St. George'southward Church, Bloomsbury, tin can exist seen, only it is a faint and distant image, and the picture is composed so information technology is the pawnbroker'due south sign, which forms a huge corrupted cantankerous for the steeple: the people of Gin Lane have called to worship elsewhere.

Townley'south verses are equally stiff in their condemnation of the spirit:

| Gin, cursed Fiend, with Fury fraught,

It enters by a deadly Draught

| Virtue and Truth, driv'northward to Despair

Simply cherishes with hellish Intendance

| Damned Loving cup! that on the Vitals preys

Which Madness to the heart conveys,

|

Beer Street [edit]

The first and second states of Beer Street featured the blacksmith lifting a Frenchman with one paw. The 1759 reissue replaced him with a joint of meat and added the pavior and housemaid.

In comparison to the sickly hopeless denizens of Gin Lane, the happy people of Beer Street sparkle with robust health and bonhomie. "Here all is joyous and thriving. Industry and jollity go hand in hand".[17] The only business that is in trouble is the pawnbroker: Mr. Pinch lives in the one poorly maintained, crumbling building in the motion-picture show. In dissimilarity to his Gin Lane counterpart, the prosperous Gripe, who displays expensive-looking cups in his upper window (a sign of his flourishing business organization), Pinch displays only a wooden contraption, perhaps a mousetrap, in his upper window, while he is forced to take his beer through a window in the door, which suggests his business is and so unprofitable equally to put the homo in fearfulness of being seized for debt. The sign-painter is besides shown in rags, simply his part in the image is unclear.

The balance of the scene is populated with doughty and good-humoured English language workers. It is George Two'due south birthday (thirty October) (indicated by the flag flying on the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields in the background) and the inhabitants of the scene are no uncertainty toasting his health. Under the sign of the Barley Mow, a blacksmith or cooper sits with a foaming tankard in one hand and a leg of beef in the other. Together with a butcher — his steel hangs at his side — they laugh with the pavior (sometimes identified as a drayman) as he courts a housemaid (the key she holds is a symbol of domesticity).

Ronald Paulson suggests a parallel betwixt the trinity of signs of sick-omen in Gin Lane, the pawnbroker, distiller, and undertaker, and the trinity of English "worthies" here, the blacksmith, pavior, and butcher. Close by a pair of fish-sellers rest with a pint and a porter sets downward his load to refresh himself. In the groundwork, two men conveying a sedan chair pause for drink, while the passenger remains wedged within, her large hoop skirt pinning her in place.[b] On the roof, the builders, who are working on the publican's house above the "Sun" tavern share a toast with the master of a tailor'southward workshop. In this image information technology is a barrel of beer that hangs from a rope above the street, in contrast to the body of the barber in Gin Lane.[18]

The inhabitants of both Beer Street and Gin Lane are drinking rather than working, but in Beer Street the workers are resting after their labours — all those depicted are in their place of piece of work, or have their wares or the tools of their trade near them — while in Gin Lane the people drink instead of working.[19] Exceptions to this dominion come up, most obviously, in the course of those who profit from the vice in Gin Lane, but in Beer Street Hogarth takes the opportunity to make another satirical statement. Aside from the enigmatic sign-painter, the merely others engaged in work in the scene are the tailors in an attic. The wages of journeyman tailors were the subject of an ongoing dispute, which was finally settled by arbitration at the 1751 July Quarter sessions (in the journeymen's favour). Some believe that the tailors serve another purpose, in that Hogarth shows them standing to toil while all the other inhabitants of the street, including their main, pause to refresh themselves.[nineteen] Much as the tailors are ignored by their master and left to continue working, the occupants of Beer Street are oblivious to the suffering on Gin Lane.

Hogarth also takes the opportunity to comment on artistic pretensions. Tied up together in a basket and destined for use every bit scrap at the torso-maker are George Turnbull'southward On Aboriginal Painting, Hill on Royal Societies, Modernistic Tragedies, Polticks vol. 9999 and William Lauder'southward Essay on Milton'southward Apply and Imitation of the Moderns in Paradise Lost, all examples, existent and imagined, of the type of literature that Hogarth thought fabricated connections between fine art and politics and sought out aesthetic connections that did not exist. Lauder's piece of work was a hoax that painted Milton every bit a plagiarist.[20]

The moving-picture show is a counterpoint to the more powerful Gin Lane — Hogarth intended Beer Street to exist viewed kickoff to make Gin Lane more shocking — but it is also a celebration of Englishness and depicts of the benefits of beingness nourished by the native beer. No foreign influences pollute what is a fiercely nationalistic image. An early impression showed a scrawny Frenchman beingness ejected from the scene by the burly blacksmith who in later on prints holds aloft a leg of mutton or ham (Paulson suggests the Frenchman was removed to prevent confusion with the ragged sign-painter).[21]

In that location is a celebration of English language industriousness in the midst of the jollity: the two fish-sellers sing the New Carol on the Herring Fishery (by Hogarth's friend, the poet John Lockman), while their overflowing baskets bear witness to the success of the revived industry; the Male monarch'south speech communication displayed on the table makes reference to the "Advancement of Our Commerce and the cultivating Fine art of Peace"; and although the workers take paused for a break, it is clear they are non idle. The builders have not left their workplace to drink; the primary tailor toasts them from his window simply does non leave the attic; the men gathered around the table in the foreground take not laid their tools aside. Townley's patriotic verses farther refer to the contrast between England and France:

| Beer, happy Produce of our Island

And wearied with Fatigue and Toil

| Labour and Fine art upheld by Thee

We quaff Thy mild Juice with Glee

| Genius of Health, thy grateful Taste

And warms each English generous Breast

|

Paulson sees the images every bit working on different levels for unlike classes. The middle classes would have seen the pictures as a straight comparing of adept and evil, while the working classes would have seen the connection between the prosperity of Beer Street and the poverty of Gin Lane. He focuses on the well-fed woman wedged into the sedan chair at the rear of Beer Street as a cause of the ruin of the gin-addled woman who is the principal focus of Gin Lane. The costless-market economy espoused in the Male monarch'due south address and practised in Beer Street leaves the exponents prosperous and corpulent only at the same time makes the poor poorer. For Paulson the 2 prints describe the results of a move abroad from a paternalistic state towards an unregulated market economy. Farther, more than direct, contrasts are made with the woman in the sedan chair and those in Gin Lane: the adult female fed gin as she is wheeled habitation in a barrow and the dead adult female beingness lifted into her coffin are both mirror images of the hoop-skirted woman reduced to madness and death.[22]

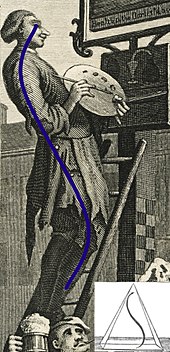

Sign-painter [edit]

Paulson suggests that sign-painter's opinion forms what Hogarth chosen the "Line of Beauty" (Hogarth's example inset).

The sign-painter is the about difficult figure of the two images to characterise. He appeared in preliminary sketches as another jolly fat archetype of Beer Street—but by the time of the first print, Hogarth had transformed him into a threadbare, scrawny, and somewhat dreamy character who has more than in common with the inhabitants of Gin Lane than those who populate the scene below him.[ix] Most simply, he may be a subtle aside on the artist'south status in society—he carries the palette that Hogarth fabricated his trademark, which appears in several of his cocky-portraits.[23]

However he is painting a sign advertising gin, so his ragged advent could equally reflect the rejection of the spirit past the people of Beer Street. He may besides exist a resident of Gin Lane, and Hogarth includes him as a connection to the other scene, and as a suggestion that the government's initial policy of encouraging the distillation of gin may be the crusade of both Gin Lane'southward ruin and Beer Street's prosperity. He is ignored by the inhabitants of Beer Street equally they ignore the misery of Gin Lane itself.[24] Paulson suggests that he is the lone "cute" figure in the scene. The corpulent types that populate Beer Street later featured as representations of ugliness in Hogarth's The Analysis of Dazzler, while the painter, every bit he leans back to adore his work, forms the serpentine shape that Hogarth identified every bit the "line of dazzler".[21]

Thomas Clerk, in his 1812 The Works of William Hogarth, writes that the sign-painter has been suggested equally a satire on Jean-Étienne Liotard (chosen John Stephen by Clerk), a Swiss portrait painter and enameller whom Horace Walpole praised for his attention to item and realism, mentioning he was, "... devoid of imagination, and one would think retention, he could render nil but what he saw before his eyes."[25] In his notes in Walpole'southward Anecdotes of painting in England, James Dallaway adds a footnote to this statement about Liotard saying, "Hogarth has introduced him, in several instances, alluding to this want of genius."[26] However, Liotard was wearing a full beard, as his self-portrait of 1746 shows.

Influences [edit]

Beer Street and Gin Lane with their depictions of the deprivation of the wasted gin-drinkers and the corpulent good health of the beer-drinkers, owe a debt to Pieter Bruegel the Elder's La Maigre Cuisine and La Grasse Cuisine engraved by Pieter van der Heyden in 1563, which shows two meals, one of which overflows with food and is populated past fat diners, while in the other the emaciated guests squabble over a few meagre scraps. Brueghel'southward compositions are as well mirrored in the layers of detail in Hogarth'southward two images.[27] [28]

Inspiration for these two prints and The Four Stages of Cruelty probably came from his friend Fielding: Hogarth turned from the satirical wit of Marriage A-la-Mode in favour of a more than cutting examination of criminal offense and punishment with these prints and Manufacture and Idleness at the aforementioned time that Fielding was approaching the subject in literature.[29] Paulson thinks information technology likely that they planned the literature and the imagery together as a campaign.[8]

Reception [edit]

Charles Lamb picked out this particular of a funeral procession in Gin Lane equally a mark of Hogarth's skill: "extending of the interest across the bounds of the subject area could simply have been conceived by a corking genius".[thirty]

Charles Knight said that in Beer Street Hogarth had been "rapt across himself" and given the characters depicted in the scene an air of "tipsy jollity".[31] Charles Lamb considered Gin Lane sublime, and focused on the almost invisible funeral procession that Hogarth had added beyond the jerry-built wall at the rear of the scene as mark of his genius. His comments on Gin Lane formed the centre of his argument to rebut those who considered Hogarth a vulgar artist because of his pick of vulgar subjects:

There is more of imagination in it-that power which draws all things to one,-which makes things animate and inanimate, beings with their attributes, subjects and their accessories, take one color, and serve to one effect. Every thing in the print, to use a vulgar expression, tells.

Every role is full of "foreign images of death." It is perfectly amazing and phenomenal to expect at.[30]

The critic William Hazlitt shared Lamb'southward view that Hogarth was unfairly judged on the coarseness of his subject affair rather than for his skill equally an artist. He singled out Gin Lane and The Enraged Musician as detail examples of Hogarth'south imagination and considered that "the invention shewn in the great style of painting is poor in the comparison".[32]

Both John Nichols and Samuel Felton felt that the inclusion of Turnbull's work in the pile of scrap books was harsh, Felton going as far as to suggest Hogarth should accept read it before condemning information technology.[33]

After the Tate Great britain's 2007 exhibition of Hogarth'due south works the art critic Brian Sewell commented that "Hogarth saw it all and saw it directly, without Rowlandson'south gloss of puerile humour and without Gainsborough'south gloss of sentimentality," merely in a piece titled Hogarth the Ham-fisted condemned the heavy-handedness and lack of subtlety that made his images an "over-emphatic rant in his rough insistence on excessive and repetitive detail to reinforce a point."[34]

The reception by the general public is hard to gauge. Certainly one shilling put the prints out of attain for the poorest people, and those who were pawning their clothes for gin money would not be tempted to buy a print, only in that location is evidence that Hogarth's prints were in wide circulation even among those that would have regarded them as a luxury, and there are records from the 18th century indicating that his works were used for moral instruction by schoolmasters.[35] At any charge per unit, the Gin Act — passed in no small mensurate as the outcome of Fielding and Hogarth's propaganda — was considered a success: gin product fell from seven million royal gallons (32,000,000 L) in 1751 to 4.25 million majestic gallons (19,300,000 L) in 1752, the everyman level for 20 years.[36] By 1757, George Burrington reported, "We do not run across the hundreth part of poor wretches drunk in the street".[37] Social changes, quite apart from the Gin Act (amidst them the increase in the price of grain after a series of bad harvests) were reducing the dependence of the poor on gin, but the trouble did non disappear completely: in 1836, Charles Dickens all the same felt it an important enough issue to repeat Hogarth's observations in Sketches by Boz. Like Hogarth, Dickens noted that poverty rather than gin itself was the crusade of the misery:

A later engraving of Beer Street by Samuel Davenport (probably for Trusler's Hogarth Moralized) had slight variations from all of the Hogarth states.[c]

Gin-drinking is a bully vice in England, but wretchedness and dirt are a greater; and until y'all improve the homes of the poor, or persuade a half-famished wretch not to seek relief in the temporary oblivion of his ain misery, with the pittance that, divided among his family unit, would furnish a morsel of staff of life for each, gin-shops will increment in number and splendour.

The vast numbers of prints of Beer Street and Gin Lane and The Iv Stages of Cruelty may accept generated profits for Hogarth, but the wide availability of the prints meant that private examples did not generally command loftier prices. While there were no paintings of the two images to sell, and Hogarth did not sell the plates in his lifetime, variations and rare impressions existed and fetched decent prices when offered at auction. The outset (proof) and 2d states of Beer Street were issued with the image of the Frenchman existence lifted by the blacksmith, this was substituted in 1759 by the more than commonly seen third state in which the Frenchman was replaced by the pavior or drayman fondling the housemaid, and a wall added behind the sign-painter. Prints in the first land sold at George Bakery'south sale in 1825 for £2.10s,[d] merely a unique proof of Gin Lane with many variations, particularly a blank area under the roof of Kilman's, sold for £xv.15s. at the same auction.[e] Other pocket-sized variations on Gin Lane exist – the 2nd state gives the falling child an older face, perhaps in an effort to diminish the horror,[38] simply these too were widely available and thus inexpensive. Copies of the originals past other engravers, such as Ernst Ludwig Riepenhausen, Samuel Davenport, and Henry Adlard were as well in broad circulation in the 19th century.

Modernistic versions [edit]

The iconic Gin Lane, with its memorable limerick, has lent itself to reinterpretation by mod satirists. Steve Bong reused it in his political cartoon Free the Spirit, Fund the Party, which added imagery from a Smirnoff vodka commercial of the 1990s to reveal the and so Prime number Minister, John Major, in the role of the gin-soaked woman letting her infant autumn,[39] while Martin Rowson substituted drugs for gin and updated the scene to characteristic loft conversions, wine bars and mobile phones in Cocaine Lane in 2001.[40] There is likewise a Pub Street and Binge Lane version, which follows closely both the format and the sentiment of Hogarth's originals.[41] In 2016 the Royal Social club for Public Wellness commissioned artist Thomas Moore to re-imagine Gin Lane to reflect the public health issues of the 21st Century. The work is displayed in the Foundling Museum, London.

Notes [edit]

The woman in the sedan chair appeared in Hogarth's before Taste in High Life.

a. ^ The snuff may exist a reference to Fielding, who was renowned as a heavy snuff taker.[42]

b. ^ This woman appeared as she does here, wedged into a sedan chair with her hoop skirt pinning her in place, equally the subject of a painting displayed in Hogarth'southward Sense of taste in High Life, a forerunner to Marriage à-la-mode commissioned by Mary Edwards around 1742.[43]

c. ^ While Davenport'south engraving of Gin Lane is a faithful reproduction of Hogarth'southward original there are multiple small variations in his engraving of Beer Street: noticeably, elements from different states are mixed, and lettering is contradistinct or removed on the copy of the Rex's oral communication and the scrap books.

d. ^ Baker had bought a number of Hogarth'due south works at Gulston's sale in 1786 where the first state prints of Gin Lane and Beer Street sold for £ane.7s. Whether they were bought past Baker straight is not recorded.[38]

e. ^ Compare this with the iv plates of 4 Times of the Day, which sold for £six.12s.6d.,[44] and a unique proof of Taste in High Life, which went for £four.4s.[45] A proof (probably unique) of the print of Hogarth'south self-portrait (with his pug) Gulielmus Hogarth 1749 sold for £25.[46]

References [edit]

- ^ Dillon p.15

- ^ Dillon p.13

- ^ Dillon p.69

- ^ Dillon p.122

- ^ Warner p.131

- ^ Quoted in Paulson (Vol.three) p.25

- ^ Loughrey and Treadwell p.xiv

- ^ a b Paulson (Vol.3) p.17

- ^ a b Uglow p.499

- ^ George p.41; tape of the trial of Judith Defour.

- ^ executedtoday.com;Details of the crime

- ^ a b Warner p.69

- ^ Dillon p.42

- ^ Clerk p.29

- ^ Clerk p.28

- ^ Clerk p.28

- ^ Hogarth p.64

- ^ Uglow p.497

- ^ a b Paulson (Vol.3) p.25

- ^ Paulson (Vol.three) p.34

- ^ a b Paulson (Vol.iii) p.33

- ^ Paulson (Vol 3) pp. 24–25

- ^ Hallett p.192

- ^ Hallett p. 192

- ^ Clerk p. 25

- ^ Dallaway in Walpole p. 747

- ^ Bindman p.180

- ^ Paulson (Vol.3) p.24

- ^ Hallet p.181

- ^ a b Lamb

- ^ Knight p.6

- ^ Hazlitt p.301

- ^ Felton p.66

- ^ Sewell. Evening Standard

- ^ Bindman p.183

- ^ Dillon p.263

- ^ Quoted in Dillon p.263

- ^ a b Hogarth p.233

- ^ Hallett p.37

- ^ Riding, The New York Times

- ^ "SIBA: Brewers call on Hogarth". Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Paulson (2000) p.284

- ^ Paulson (Vol.2) p.204

- ^ Hogarth p.199

- ^ Hogarth p.212

- ^ Hogarth p.227

Sources [edit]

- Bindman, David (1981). Hogarth. Thames and Hudson. ISBN0-500-20182-X.

- Clerk, Thomas (1812). The Works of William Hogarth. Vol. 2. London: Scholey.

- Dillon, Patrick (2004). Gin: The Much Lamented Decease of Madam Geneva the Eighteenth Century Gin Craze. Justin, Charles & Co. ISBN1-932112-25-one.

- Felton, Samuel (1785). An Caption of Several of Mr. Hogarth's Prints. London: J.Walter.

- Gay, John (1986). Bryan Loughrey and T. O. Treadwell (ed.). The Ragamuffin'south Opera. Penguin Classics. ISBN0-14-043220-5.

- George, M. Dorothy (1985). London Life in the Eighteenth Century. University Chicago Publications. ISBN0-89733-147-8.

- Hallett, Mark; Riding, Christine (2006). Hogarth. Tate Publishing. ISBN1-85437-662-four.

- Hazlitt, William (1999). Selected Writings. Oxford Academy Press, USA. ISBN0-nineteen-283800-8.

- Hogarth, William (1833). "Remarks on diverse prints". Anecdotes of William Hogarth, Written by Himself: With Essays on His Life and Genius, and Criticisms on his Work. J.B. Nichols and Son.

- Knight, Charles (1843). London. London: Charles Knight and Co.

- Lamb, Charles (1811). "On the genius and grapheme of Hogarth: with some remarks on a passage in the writings of the tardily Mr. Barry". The Reflector. two (three): 61–77. Archived from the original on two March 2008.

- Paulson, Ronald (1992). Hogarth: Loftier Art and Low, 1732–50 Vol 2. Lutterworth Press. ISBN0-7188-2855-0.

- Paulson, Ronald (1993). Hogarth: Art and Politics, 1750–64 Vol 3. Lutterworth Press. ISBN0-7188-2875-5.

- Paulson, Ronald (2000). The Life of Henry Fielding. Blackwell Publishing. ISBN0-631-19146-1.

- Riding, Alan (31 May 2006). "Pfft: Satirical Pinpricks Deflating Pomposity and Power". New York Times. Archived from the original on 19 April 2011. Retrieved 8 Feb 2008.

- Sewell, Brian (9 February 2007). "Hogarth the Ham-fisted". Evening Standard. Archived from the original on half-dozen February 2008. Retrieved 13 February 2008.

- Trusler, John (1833). The Works of William Hogarth. London: Jones and Co.

- Uglow, Jenny (1997). Hogarth: A life and a earth. New York: Farrar Straus Giroux. ISBN0-374-52851-ix.

- Walpole, Horace (1849). Anecdotes of painting in England, with some account of the chief artists. London: Henry G. Bohn.

- Warner, Jessica (2002). Craze: Gin and Immoderacy in an Age of Reason. Thunder's Mouth Press. ISBN1-56858-231-5.

External links [edit]

- Discussion by Janina Ramirez and Lars Tharp: Art Detective Podcast, 11 January 2017

Beer Street And Gin Lane,

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Beer_Street_and_Gin_Lane

Posted by: jostviong1977.blogspot.com

0 Response to "Beer Street And Gin Lane"

Post a Comment